Your cart is currently empty!

INTERVIEW | Xueyuan Wang + Justin Fan

Featuring Projects : Gypsum to Gypsum

Xueyuan Wang is a practicing architecture and urban designer based in New York, known for her thoughtful approach to design and her contributions to meaningful architectural and urban projects. With seven years of experience, she has played an integral role in shaping projects across the United States, including industrial zone redevelopment, adaptive reuse of historic structures, school campuses, and waterfront revitalization. Her work demonstrates a strong focus on civic architecture, public spaces, and urban infrastructure, reflecting her dedication to improving the quality of urban life.

Xueyuan has been recognized for her ability to address complex urban challenges with innovative and sustainable strategies. As a key participant in projects of high distinction, her contributions have earned acknowledgment from respected organizations and professionals in the field. Her work often prioritizes inclusivity and community needs, underscoring her commitment to socially impactful design.

Beyond her practice, Xueyuan actively engages in architectural research and public dialogue. She was recently invited to present her insights on polycentric urban development and its implications for migrant populations at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs. Her professional experience includes contributing to high-profile projects at Diller Scofidio + Renfro in New York and Gensler in Shanghai, where her expertise has helped shape innovative urban and civic spaces.

Justin Fan is currently practicing as an architectural designer and project manager in a residential boutique firm with a fellow alumna. He graduated magna cum laude from Rice University with a Bachelor of Arts in Architecture and a Bachelor of Architecture in 2021 and 2023 respectively. In his second year, Justin was awarded the Mary Ellen Hale Lovett Traveling Fellowship to study and document the void deck typology in Singapore’s public housing blocks and its attitude towards urbanism, climate change, and “functional indeterminacy” as described by Ooi and Tan (1992). Through this travel fellowship, he appreciated the community-oriented perspective on how to design the ground plane as an environment preserved for the public. In his fourth year of study, Justin designed an artist-in-residence gallery and studio with a focus on the enfilade as a radical embrace of public space that eschews dedicated circulation and single-point entry. He was awarded the second prize of the William Ward Watkin Fellowship for this project titled On-Off Enfilade, as he also explored architectural representation through animation and digital cinematography.

Justin worked at Thomas Phifer and Partners in New York City upon completing his first degree, where he joined the team designing the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw. Justin collaborated on designing details and reviewing concrete formwork shop drawings to coordinate device locations and joint patterns. Last October, Justin was invited to attend the grand opening ceremony of the museum in Poland and had the surreal opportunity to walk through a meticulously designed project that he contributed to.

Currently based in Texas, Justin has recently completed his experience requirement for licensure and is studying for the Architect Registration Exam. He believes that architectural design should maintain a graceful modesty in its relationship to the built work’s setting and contribute to a public-facing urbanism and preservation of landscape. Recently, Justin has returned to vernacular precedents as culturally rich evolutions of typology to inform an aesthetic language derived from tested functionality and accessibility.

During the semester of study abroad in Paris, Justin and Xueyuan collaborated on their proposal, Gypsum to Gypsum, for the adaptive reuse of a historic gunpowder factory in a forested park. Xueyuan and Justin complemented one another’s skills and sensibilities, continuing a naturally developed friendship of peer-feedback. The project has been awarded the AIA Continental Europe Design Award 1st Prize in student category, and the Margaret Everson-Fossi Fellowship for the best design project in the advanced option studios.

1.What specific historical or cultural significance does the gunpowder factory site hold in the context of the surrounding community, and how did you approach preserving its history while introducing new functions?

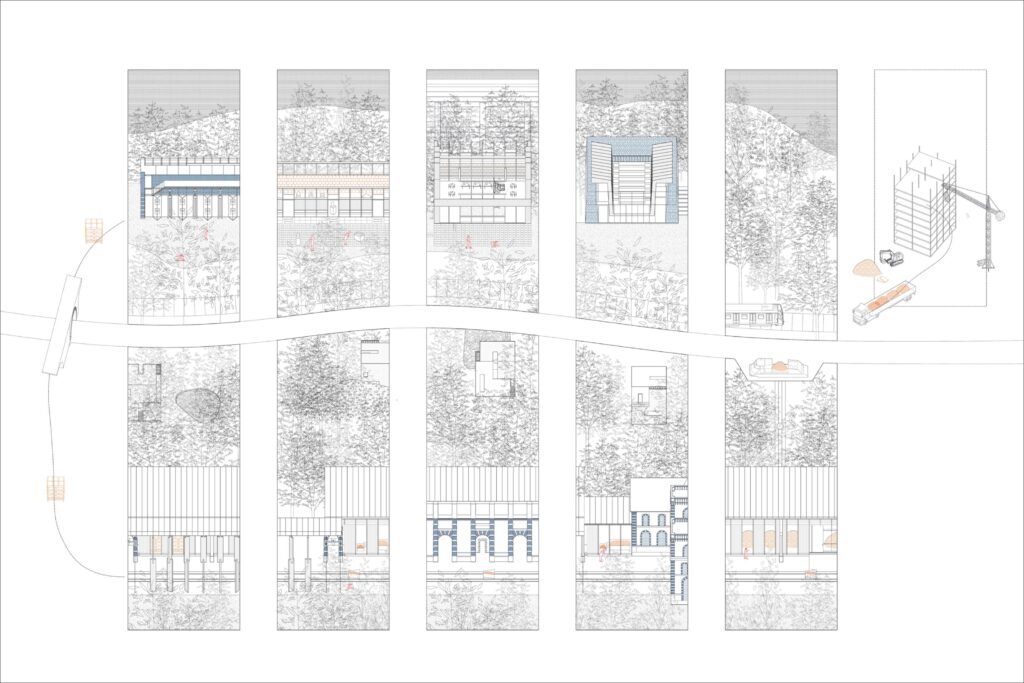

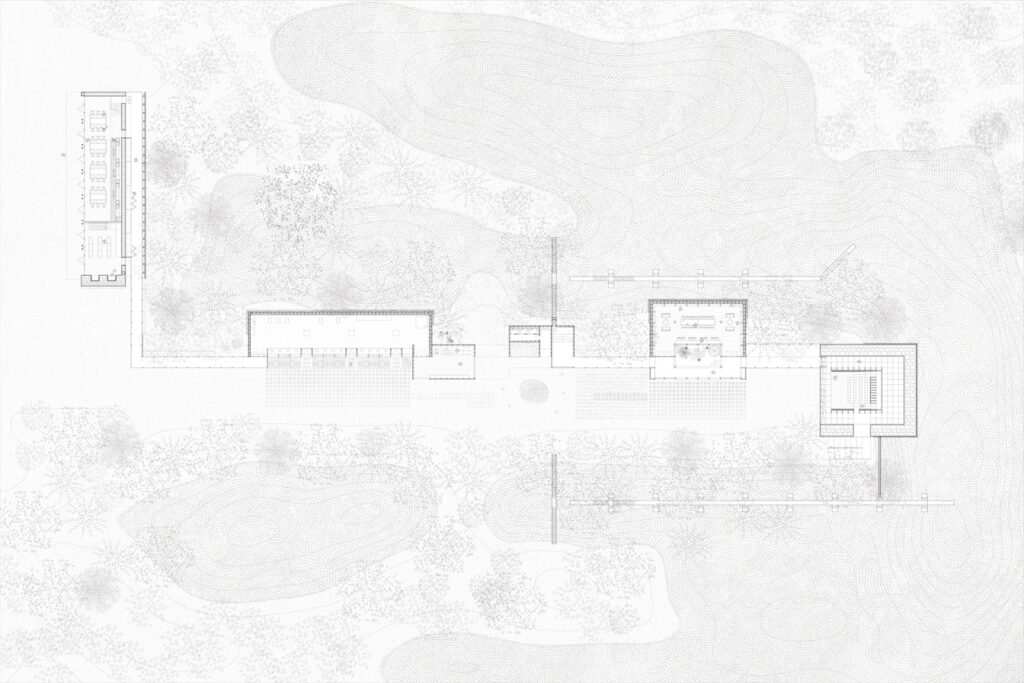

The Parc forestier de la Poudrerie is a forested historic gunpowder manufacturing complex that operated from 1873 to 1973, capable of producing up to 28 tons of munitions per day. Today, it is a lush county park punctuated by open lawns, historical vestiges, tranquil ponds, and a small museum memorializing its legacy. The park is located in the Sevran neighborhood northeast of central Paris, at a junction that also welcomes residents from the Livry-Gargan, Villepinte, and Vaujours neighborhoods.

Our first impression of the site was the contrast between its volatile original function and the peaceful scenery today – children riding bicycles and families having picnics on the lawn against a backdrop of deteriorating historic stone structures. We want to capture the site’s industrial history, but at the same time transform it to celebrate its current use as a neighborhood park.

Our proposal transforms the site into a gypsum recycling factory, producing pure gypsum powder from construction waste material. The gypsum powder then becomes a renewed material for ceramic arts. While gunpowder is designed to destroy, ceramic vessels are designed to preserve. Gunpowder is a volatile compound while ceramics is a delicate artifact. By exploring the poetic polarity of these two materials and the process of making them from the earth, we seek to give the site and its historic structures a new life.

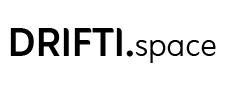

2.You mention the project’s scale, from metropolitan considerations down to intimate details. How did you manage the scale shift in terms of design process and coordination between large-scale planning and the specific interventions on-site?

Before we start proposing programs or architectural design, we did a thorough walk through the neighborhood supplemented by thorough research of the surrounding context. We studied the local urban planning policies, mapped out the city’s existing and proposed development plan in the next decades, and referenced the geological relationship to the gypsum deposits around the site. The site is located along the Canal de l’Ourcq in the Greater Paris area. Under the Grand Paris Project, a city regeneration project, large quantities of housing construction will take place along the canal phased over the next 30 years. With the city’s emphasis on sustainable development, we start to ponder how to balance such a grand scale of construction with the sustainable goals.

These ideas synthesized when we thought of the recycling factory as a project program. On the urban scale, it supports the city’s interest in sustainability and connects to central Paris by the canal, a piece of infrastructure that would now transport the construction waste. On a neighborhood scale, the site is surrounded by educational and cultural buildings, including nurseries, high schools and colleges. The metro station also brings people in from other communes or central Paris. Hence beyond the industrial processing of material, we also envision the cultural aspect of our community-minded program to be suited for all ages and user groups, for ceramics making, educational events, artist studios, and art exhibitions.

The idea of environmental sustainability and creating a visitor friendly experience flows through our entire design process, down to the architectural details. We want to maximize the preservation of the existing and allow the inhabitants to be aware of that history while seeing the constant regeneration of material life cycle on site.

3.How did you address the site’s physical and programmatic decay? Were there any particular structural or aesthetic elements from the existing ruins that you intentionally preserved, and how did you integrate them with new elements?

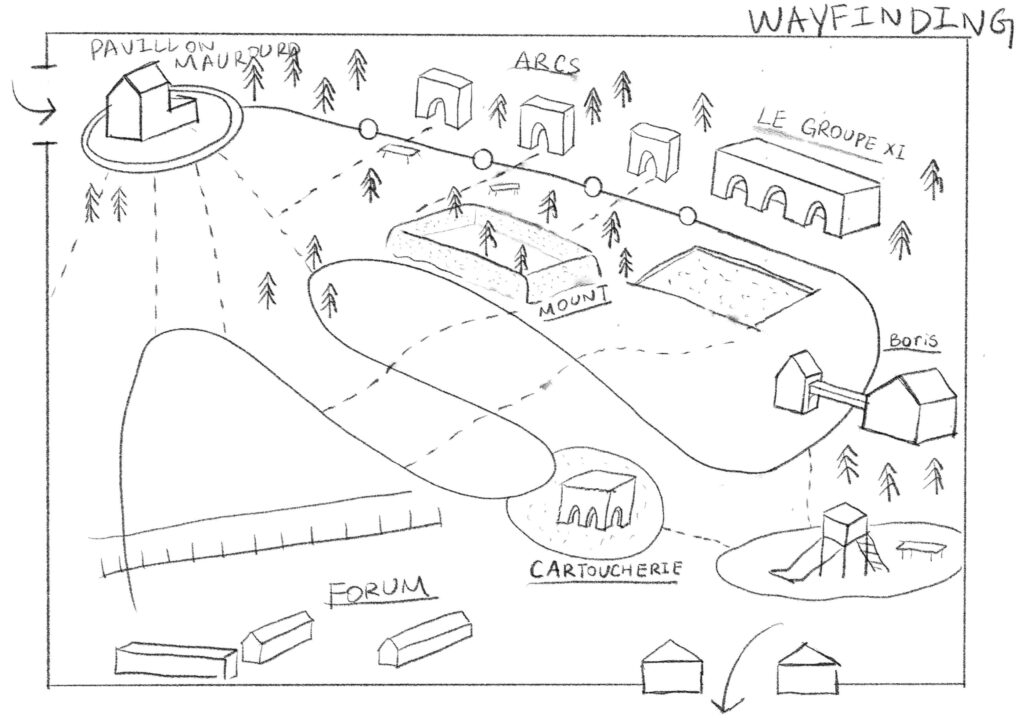

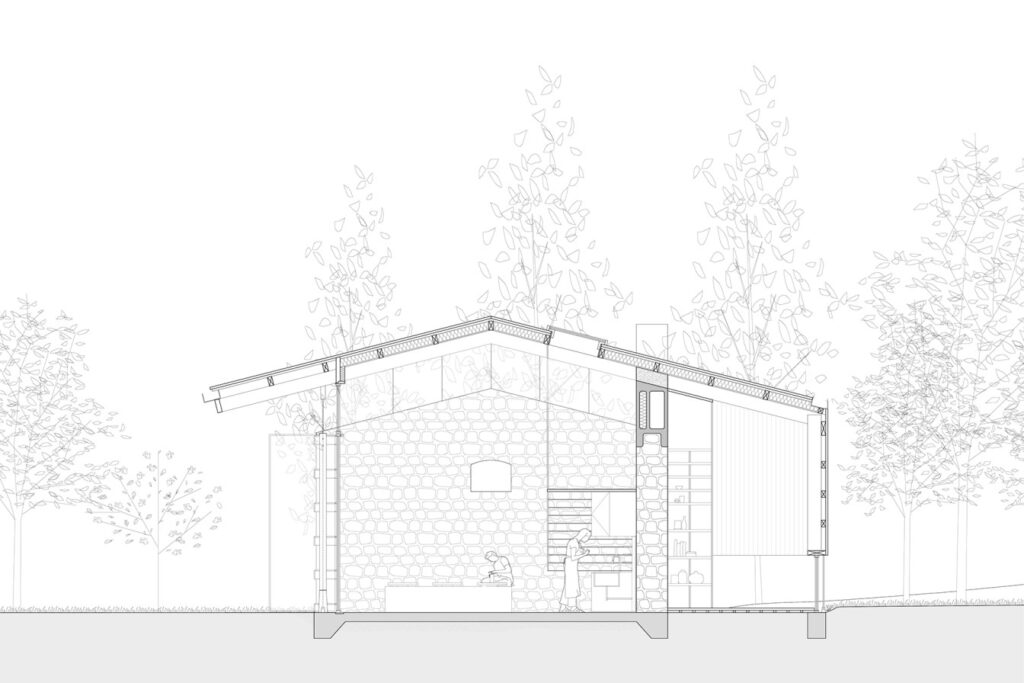

Recognizing the massive quality of the existing structures, we adopted an overall strategy for preserving all the stone structures by treating them as the structure and foundations. Newly installed glue-laminated wood structure then sits on top to create inhabitable space.

For example, we studied the structural diagram of each historic building and devised different architectural strategies. The arches are structurally robust as bases on top of which we designed a Y-shaped beam to hold the roof structure. Tension cable systems were chosen for a minimal material presence that still anchored the roofs to resist lift.

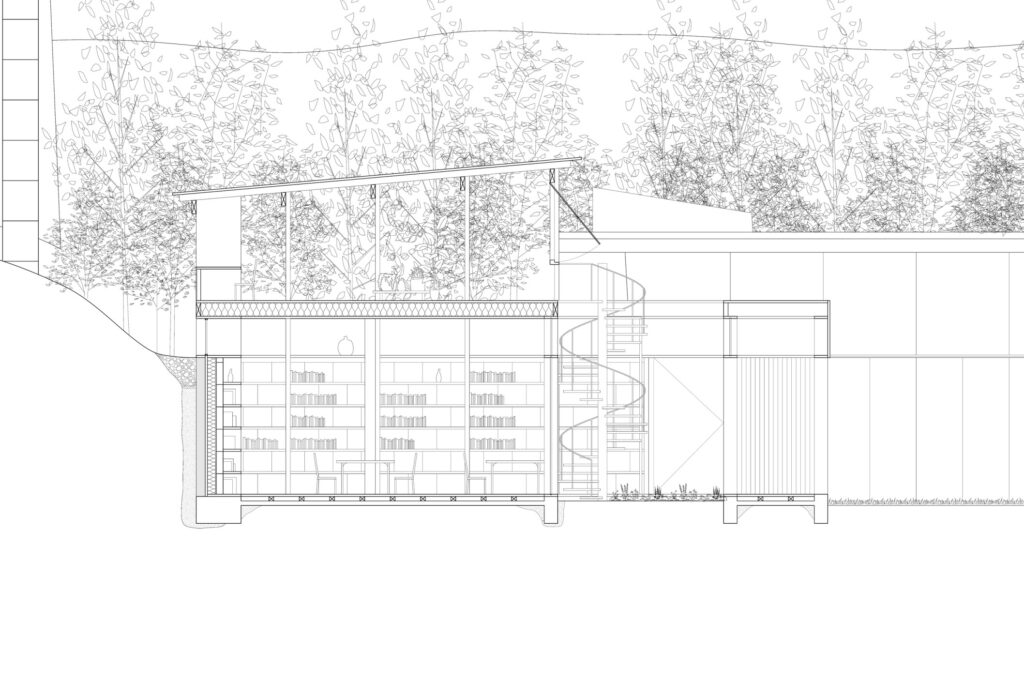

On the north side, we took advantage of the massive concrete walls of the bunker as an abundance of structure and insulation for the newly interiorized space. A cradle structure constructed with glue-lam beam and timber framing holds the auditorium seating in a stepping configuration. To avoid cutting through the existing post-tensioning cables in the slab that forms the bunker’s roof, we established a secondary structural grid for cutting out holes in between post-tensioning cables and insert the wood structure through the cutouts. The cutouts then become skylight opportunities for natural light, which filters through the louvers in between the glulam beams. The diffuse creates a soft glowing atmosphere in the auditorium. Bench seating descends from its highest point at the back of the bunker towards the lawn and is accessed through an existing opening on the side of the bunker wall. The front facade of the bunker is enclosed with a double glazed wall, and operable panels enable the space to open up to enjoy the shaded greenspace.

4.How did you balance the challenge of preserving the integrity of the aging stone structures with the need for sustainable intervention? Were there any particular design strategies or materials you used to achieve this?

As mentioned above, we maintained and reinforced any structural elements that supported the aging stone structures, and adopted design strategies that touch the existing stone in a light manner.

In terms of sustainability, by reusing the existing stone walls, which are massive carbon dioxide emitters, we manage to avoid the large quantity of carbon emissions and lower our overall carbon footprint for the new building parts. For the structural additions, we selected cross-laminated timber (CLT) as the main material. CLT is a strong material and is recyclable once all the metal components are stripped off. The second phase of the project, comprising the gallery and the library on the north side, uses gypsum block, the product of the recycling factory on the south side, as interior surface cladding. We produced a series of architectural detail drawings showing our material choice, structural connection, and the amount of carbon emission we are able to avoid through these design choices.

5.Sustainability is a central theme of the project. Could you elaborate on the sustainable design choices you made in terms of material sourcing, energy efficiency, and long-term adaptability?

On a macro-scale, the proposed program itself as an educational recycling factory is a manifestation of sustainable practice. The cycle of gypsum as a material starts from the construction sites under the Grand Paris Project. Waste materials like plaster walls are transported from the construction site to the ports along the canal and then to the park’s receiving dock. The waste plaster walls are then transferred by carts that run along existing railways to the storage space in the factory. As the gypsum powder is going through the recycling process, visitors are free to walk along the path and look at the industrial procedures. At the end of the factory, pure gypsum powder get packaged and transferred to the northside, where the cultural infrastructures are.

The gypsum powder is used for molding ceramics projects in the ceramics workshop, which produces artworks that are then exhibited in the adjacent gallery space. A library and an auditorium provides infrastructure for educational or communal events. Envisioned to be built as a second phase in the project, the gallery and the library use gypsum blocks made from the recycled gypsum powder as interior walls.

The entire project aims to exhibit both the product and the process of material life regeneration.

On a construction detail level, specific design decisions are made based on sustainability concerns. The workshop, adapted from an original cannon shed, uses the existing stone wall as structural base and glulam beam to elevate the roof. The enclosed portion of the workshop is divided into the ceramics making space and the kiln room. In the latter, two kilns for firing ceramic works are located within the thickest side of the wall, and the heat is directed through a tunnel, contained in a series of precast concrete and exit the building through a chimney. The heat generated by the firing kiln is reused for drying new ceramics works. As the heat travels through the precast concrete tunnel, wood fiber insulation on the inside of the tunnel prevents heat loss into the workshop. This enables the heat to be released to dry and preheat the ceramic works stored in the glass cabinet, preparing them to be ready for the firing procedure.

6.What role did the surrounding environment and natural elements, such as landscape and local ecology, play in your design approach? Did the park’s natural features inform the way you approached circulation, restoration, and new interventions?

The project utilizes the Canal de l’ourcq as transportation backbone for construction waste. The project receives the gypsum waste produced from construction sites through the canal, and recycles them into pure gypsum powder for constructing new facilities on site, and for daily use in the ceramics studios.

In addition to that, the rich underground gypsum deposits in Paris, especially around the Vaujour area, provided us this proximity to several gypsum quarries. The proximity to Cycle Terre, a displaced earth recycling factory, and to the quarries that could produce gypsum waste well situated our project for material recycling.

At the architectural scale, our design also maximizes the advantage of existing topography on site.

On the south side, the clear path lined up by the trees, railway and existing arches informed the unique linear form of the recycling factory.

On the north side, the site for the cultural infrastructures enjoys pleasant natural shading created by the densely wooded “mounds”. These man-made steep hills of earth were originally set in an elongated horseshoe around the concrete bunker as a safety measure for test-firing cannons and guns. The library and the gallery are designed as two volumes sitting into the existing mound and open up to the central lawn. Designs such as the second floor terrace of the library and the operable panels on the gallery facade create sheltered outdoor space for visitors to have direct contact with nature. As a result, the landscape is also designed for a delightful outdoor experience under pleasant weather. The porcelain pavers sit lightly on the grass, providing dry surfaces for people to hangout or outdoor ceramics exhibitions. This way, visitors could enjoy a rich variety of spaces, from indoor, semi indoor to outdoor space for both the gallery and the library. In between the gallery and the library, a small mound covered with grass sits across this sheltered gathering space so that children could have their little adventures on the mound while their parents observe nearby.

7.Can you discuss any challenges or surprises you faced in working within a European urban context after your studies in the U.S.? How did your design approach evolve or adapt when dealing with the different cultural or urban challenges?

We are definitely impressed by the implication of sustainability policies and goals on European urbanism, design industry and even life in general, especially when Paris is at the center of the global climate discourse, a city that is currently pursuing the Paris Climate Action Plan.

When considering “urbanism” or “suburbanization” in a U.S. context, the 1950s suburbanization movement comes to mind—a car-centric shift of middle-class families to the outskirts in search of larger spaces and an improved lifestyle. In contrast, suburbanization in the Greater Paris region tells a different story. The suburbs accommodate large housing projects, often home to residents displaced from the city center, and rely heavily on public transportation networks.

Our project, Gypsum to Gypsum, was proposed in parallel with Paris’s Grand Paris Express—an ambitious transit project expanding the metro network to better connect the Greater Paris area. This juxtaposition of suburbanization patterns and sustainability priorities presented a unique design context.

In this setting, integrating our design with existing and future transportation infrastructure while addressing carbon emission goals became both a challenge and an opportunity. The experience required us to adapt our design approach to prioritize connectivity, sustainability, and the nuanced social dynamics of the Parisian suburbs, ultimately enriching our perspective on architecture and urban design.

8.How did the collaboration between the two of you shape the final design? Were there any key moments or differences in perspective that led to critical decisions or new insights?

Our collaboration was blessed with our complementary strengths, with each of us bringing a unique focus to the design process. Justin excelled in exploring architectural forms and tectonics, delving into the materiality and spatial experience of the project. Meanwhile, Xueyuan concentrated on synthesizing the broader urban context and shaping the overall planning framework. This balance allowed us to develop a well-rounded design scheme that addressed both the macro and micro scales of the project.

One pivotal insight came as we faced the challenge of the limited design timeframe. We had to prioritize which aspects of the design to represent most effectively. By combining Justin’s attention to detail in architectural representation with Xueyuan’s focus on urban strategy, we crafted a narrative that emphasized the project’s life cycle, from material sourcing to long-term adaptability. This decision not only streamlined our workflow but also underscored the interconnectedness of architectural and urban scales in achieving sustainability.

Ultimately, our collaboration maximized the value of diverse perspectives.

9.This project seems to have had a significant professional and personal impact. How has it influenced your ongoing approach to architecture, and how do you see this experience guiding your future projects or design philosophy?

Xueyuan: Through this project, I came to understand that in today’s cities, where the built environment is approaching saturation, architecture cannot exist in isolation. Buildings must contribute to and interact meaningfully with the larger urban fabric, addressing social, environmental, and infrastructural dynamics. This realization has transformed how I approach design challenges, prompting me to think beyond the boundaries of a single site and consider the ripple effects of every decision on the surrounding context.

The experience motivated me to further pursue a master’s degree in urban design, and deepened my belief in the critical importance of designing architecture in relation to its broader context—a principle that now anchors my practice. I am now working in an office that focuses on architectural and public realm design in New York City. I aim to create spaces that are not only functional and beautiful but also deeply connected to their environment and community. This philosophy will continue to shape my projects, driving me to explore innovative ways to integrate the existing architectural and urban fabric in service of more sustainable and inclusive communities.

Justin: The gypsum recycling factory set in a wooded park as an unraveled linear process represents a hybridization of architectural programs. New architecture projects will increasingly integrate complementary functions under the same roof, and we will continue to discover unexpected but intriguing pairings like industrial and cultural. Thus, as designers, we might begin to divorce specific forms with specific functions and sharpen our skills in detailing such that design excellence is expressed at the more micro scale.

10.How did your individual backgrounds or experiences influence the way you approached the project? Did either of you have any specific interests or passions that shaped particular aspects of the design?

Our individual backgrounds and experiences undoubtedly influenced the project in ways that sometimes became apparent only in hindsight. A shared understanding of the role of art and education in fostering community cohesion and enriching neighborhoods stems from our experiences learning about social responsibility.

Xueyuan: For me, children are often the first group I consider when thinking about design opportunities that serve a neighborhood. This perspective likely traces back to my high school years in Singapore, where I volunteered for after-school programs at community centers. Organizing events like mini science fairs and weekly art sessions, which frequently involved parents, families, and a broader group of citizens, gave me firsthand experience of how educational programs can bring people together, fostering a sense of community and vibrancy.

This background directly influenced our design proposal for a walkable, exhibition-like factory complemented by a series of cultural infrastructures set within a natural playground. By incorporating spaces that encourage exploration, learning, and play, we sought to create an environment that resonates across generations and cultures. Play, after all, is a universal language that transcends barriers and brings people together.

Justin: I have fostered a fascination with details. My prior work experience guided my design approach to develop a simple form with meticulous and thoughtful details. A design feature as subtle as a window’s sill relationship to the edge of the slab has profound effects on the experience of a space, even if the overall room geometry is amazingly simple. Once our project’s parti diagram had been established, much of the joy and excitement came from designing at the scale of the nearest centimeter.