Your cart is currently empty!

INTERVIEW | Claudia Almandoz

Claudia Almandoz is a self-taught, natural light photographer born in Lima, Peru, based in Mexico.

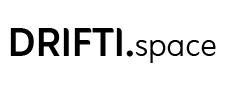

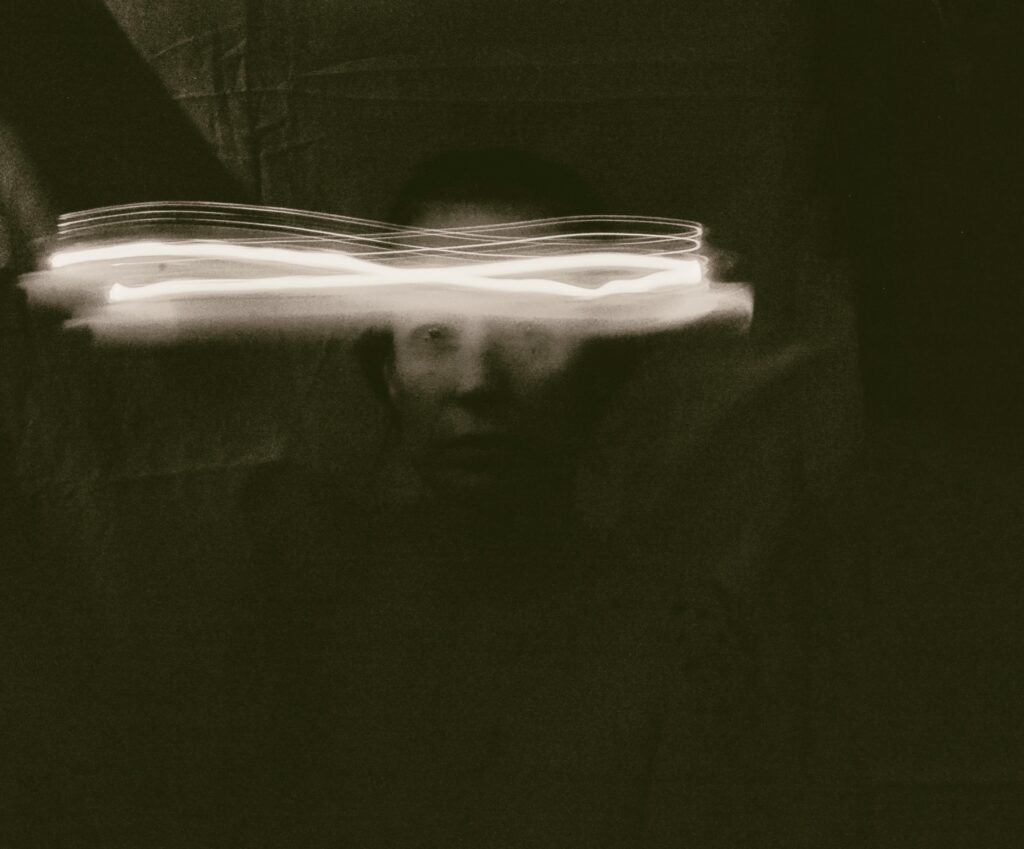

Almandoz’s artistic focus lies in the realm of self-portrait photography, where she uses the camera as her paintbrush, seeking to illuminate the depths of the human soul. Her unique approach involves a dance between physical filters, shutter speed, and ambient light, creating self-portraits that are not just captured but painted with the essence of light itself. Through this intricate interplay of technical elements, Almandoz explores the realms of shadow and the intricacies of the mind, inviting viewers to embark on a visual and emotional journey.

Beyond her personal artistic pursuits, Almandoz has lent her lens to various projects that echo her commitment to capturing the essence of life. She has undertaken independent freelance assignments across Mexico, Peru, and New Zealand.

Almandoz has collaborated with ICM Mexico on projects aimed at raising awareness for cancer. Working closely with cancer patients in Mexico City, she documented their stories with sensitivity and compassion, contributing to the broader narrative of resilience and hope in the face of adversity.

Beyond the confines of traditional art spaces, Almandoz has taken her passion to rehabilitation centers for addictions, using art as a powerful form of expression and emotional release. Today, she continues to share her knowledge and expertise through workshops, guiding others in the art of self-portraiture and collage creation.

Almandoz has studies in Art History and Interior Design, providing her with a multifaceted understanding of the visual arts. Her background, coupled with a relentless pursuit of self-discovery, has fueled her artistic journey and shaped her into the storyteller she is today.

Through the lens of self-portrait photography, I find both solace and liberation. Each click becomes a brushstroke on the canvas of my inner world, crafting images that move beyond clarity and precision to delve into the intricate tapestry of human emotion and experience. My work navigates the darker aspects of existence, while simultaneously questioning the mystic and philosophical dimensions that call to me.

By balancing physical filters, shutter speed, ambient light, and avoiding clear, crisp images, I aim to capture more than mere likeness. Each self-portrait becomes a gateway through which I explore and confront the shadows of my past—experiences shaped by trauma, abuse, and the unique complexities of being an autistic individual.

Rooted in my childhood fascination with romanticism paintings, my art serves as both a sanctuary and a canvas. It is a space where I process difficult emotions that often defy words, reclaiming my narrative by transforming pain into power and vulnerability into strength. Through these images, I seek to connect with the shared depths of our human experience, offering a visual language for what often remains unspoken.

1.Your self-portraits are often described as being “painted with light” rather than simply captured. How did you develop this approach, and what does it mean to you?

During my life, especially noticeable in my creative process as a photographer, I have always struggled with cognitive rigidity (the difficulty individuals with autism may have in adapting to changes, demonstrating, among other things, inflexible thinking). This led me to be very demanding of my own work and technique, and as a result, it took me to the mind rather than the emotion. This, in itself, caused a disconnect that, as an artist, led to distress and a feeling of lacking honesty or a voice of my own.

At some point, I came across The Artist’s Way by Julia Cameron. In practicing the exercises and following the book, I began to understand how, in my case, this rigidity was preventing me from accessing my own voice as an artist. So, I began to play with my camera, accessing the creative moment from the emotion first. And emotions can be messy. Honoring the messy aspect of it all became, not only the starting point of each creation, but also the perfect analogy and vehicle for the darker, heavier emotions I felt the need to capture. A whole new, very free universe opened up to me, one where I was no longer concerned with technical perfection, or others’ voices or opinions; a place where everything became about raw emotion, purging, and experimenting with physical filters, flashlights, candles, extremely low light conditions, reflections, and so on. I play with all of this and find the magic in being able to paint and create, with no real control over what the result may look like.

2.How do you balance the technical aspects of photography—such as filters, shutter speed, and ambient light—with the emotional and psychological depth of your self portraits?

This is part of what I “enjoy” the most. It is a challenge. I will always grab my camera and begin to capture, ignited from the inside by a deep desire, a need to purge or cry, by the very loud beckoning of a voice that demands to express emotion or thought. So, what I try to do, as I go about the very mundane process of grabbing the camera and tripod (or whatever invention I come up with to hold my camera in place), is hold the feelings and the vision in my mind. I do this with the help of music and consciously holding on to the emotion in my body through sensations. Even though in my artistic process there is an

intense amount of repetition (I can shoot up to 40 images with the timer in place, and choose only one), I seem to be able to sink deeper into the emotion with each repetition. I check the camera screen of my digital camera between each shot and adjust ISO, shutter speed, and f-stop so that it reflects the emotion, not some idea of perfection. I purposely play with blur and out-of-focus images, as the inner world is never crisp and clear. It’s more like a haze filled with voices and sensations.

3.What role does self-portraiture play in your personal journey of self-discovery and healing?

It is almost “my everything.” Part of what initially drew me to photography at the age of 13 was, on one hand, the fact that I could translate my emotions and how I saw the world into images in ways I found impossible through words. On the other hand, it allowed me to hide. I’ve always had a complicated relationship with being perceived (it goes without saying how uncomfortable standing in front of a camera is for me). But behind the lens, I was the viewer, the witness; there were secrets only I knew, and this allowed me to “not face the world” and hold a somewhat false sense of control.

As years went by, every imaginary sense of control (including the one I thought I had with my camera) fell apart. As did my life, my body, and my mind. It would be presumptuous to say that my form of artistic expression saved me. There have been endless tools that have helped me along the way. But my art gave me a sense of purpose and presence within myself that has been a lifeboat.

And so, standing in front of my own lens—in the raw, in the unsightly, and in the powerful—allows me to re-inhabit myself. I literally observe myself as a form of getting to know myself. I do not think this would be possible without the element of “ugly,” which I approach as the willingness to release the idea of what “beauty” is (which is deeply influenced by outer voices and opinions) and disengage my self-perception and value from that subjective idea. My approach to self-portraiture entails a lot of shadow work, and therefore, it is somehow a consequence, an extension of my darkness and willingness to bring it to life with respect and admiration, finding beauty in the painful and the grotesque.

4.You mention being deeply influenced by Romanticism paintings. How do you translate those visual and emotional qualities into photography?

I create from a very intuitive place, and many times, I arrive at conclusions in an “upsidedown manner.” Although many times I delve into a more philosophical side—into a world of symbolism and mysticism—this usually happens as a passionate consequence that comes after capturing the emotion through the image.

Therefore, it took me a while of intuitively creating to be hit by a déjà vu-ish feeling; a sense that the darkness, shadow, the color, and the light I was drawn to when creating seemed familiar. I then began to find a common thread between my artistic expression and the art that hung in my grandparents’ house, that emerged from their books, and my hours spent breathing it all in as a child. When this came into my consciousness, I began playing with it more purposefully. I search for more of a sense of a brushstroke than the act of capturing light.

Delving even more into my fascination for those moments of light coming up through the darkness (rather than the other way around) in those paintings was a perfect vehicle and analogy for not only my own personal process but also the way of creating that my voice had so naturally found.

If we take into consideration that Romanticism valued the individual over social conventions, believed that imagination was a gateway to spiritual truth, valued emotion over reason, the senses over intellect, and were fond of legends and fairy tales…

5.Are there specific artists, writers, or filmmakers whose work has influenced your creative vision?

Many! I’ve always been quite a visual creature, and although I am self-taught and instinctively gravitate toward experimentation and a voice of my own, I believe inspiration and the work of other artists ignite a fire within, necessary not only for one’s own artistic endeavors but also as a form of appreciation for life itself.

The first photography book I ever owned was Portraits by Richard Avedon. His work pulled me in and opened a world unknown to me before because of his unapologetic approach to the human condition. Sally Mann, Karl Blossfeldt, Vivian Maier, Witkin, Francesca Woodman, Man Ray, also open doors to alternative realities I could spend hours in. The painter Francisco Goya is a great source of inspiration and wonder for me as well. The way his art can not only graze darkness, but how it can envelope you in a world of nightmare and beauty at once, moves and inspires me.

On the other hand, many times I can be set off into an artistic process by reading or listening to music. I especially enjoy the poetry of Roberto Juarroz and Alejandra Pizarnik. And last but not least: Ethel Cain. Her music and her remorseless exploration of the underworld is absolutely breathtaking.

6.Do you see your photography as a form of self-exploration, storytelling, or activism—or a combination of all three?

A combination of all three, no doubt. I confess that the activism aspect of it was a part I came to somewhat reluctantly. I create out of necessity and impulse. Very selfishly, from a need to exorcise my demons.

But at some point, when I was still shyly sharing my work, a colleague said something to me that “stuck and cut.” He said I should be less theatrical with my work if I wanted to be taken seriously. I am deeply grateful for that comment because it ignited a fire within me that reflected perfectly that which had been trying to claw its way out of me for some

time.

What I had to say couldn’t fit solely within the personal exorcism aspect of it all anymore. I began to realize that what I captured with my camera caused discomfort because it sheds light on the consequences of abuse, subjugation, oppression, and… Up until that point, survival had led me to be quite, not rocking the boat and not being seen. Until that moment, I had not felt strong enough, or angry enough, to expose myself fully, without the need to “ask for permission to take up space.”

So, yes, at some point on my path, if I was to honor myself and be congruent, I needed to accept that my work was not only a form of self-exploration and storytelling but also activism. And I could not shy away from that anymore if I didn’t want to quell my own soul and the voice that I had worked so valiantly to ungag.

7.You’ve worked on projects with cancer patients and in rehabilitation centers. How do you see art, particularly self-portraiture, as a tool for healing and empowerment?

Self-portraiture is in itself a form of self-knowledge, but one that can be quite confronting. If I had to narrow it down to two words that express why I believe selfportrait photography to be so profound and important, it would be: chain-breaking. The

chains of societal norms, unrealistic standards, and expectations that have limited us for too long. But there’s another set of chains that often go unnoticed: the self-imposed ones.

This form of photography holds the potential to break those molds, aiding us in embracing our individuality and celebrating the beauty that radiates from within—a beauty that pertains only to oneself and that honors our essence, our life story, and our divine right to speak our “messy,” “ugly” truths.

In a world that constantly bombards us with images of “perfection” and “flawlessness,” it’s easy to forget that true beauty lies in the uniqueness of our own stories. Every line of our face, every curve, every scar tells a story of resilience and strength. It is not about conforming to a singular definition of beauty, but embracing every facet of who we are.

Self-acceptance is the liberating embrace that allows us to stand tall, unabashedly showing our true selves to the world. When we dare to accept ourselves and truly see the strength and power that lies within, we unleash a force that can move mountains. It is this very acceptance that opens the door to our innermost potential, unleashing a force that can transform.

8.How does your approach to photographing others differ from your approach to self portraiture?

When I was about 15, I was present with my camera in an indigenous ceremony here in Mexico. I quite naively and shyly walked up to a woman and asked for her permission to take her photograph with my Pentax. She passionately refused. My heart fell to the floor, feeling the full blow of rejection when I was still very unstable in my footing through this life. But I found the courage to ask her if she could just tell me why. She proceeded to tell me that if she let me take the photo, I would steal her soul, and it would be trapped within the camera.

That moment was ingrained in my memory and defines, in great part, my approach to photographing others. That day left me with an inner certainty of the deep responsibility I hold toward the person in front of my camera. I do, in fact, feel the soul of the other when I look into their eyes in that vulnerable moment in front of my lens. And so, I treat those moments with solemn respect. I feel honored, and at the same time, I feel the weight of it all.

On the other end of the spectrum is my approach to self-portraiture. I dive into the capturing of my own image with a complete loss of fear or care. On the contrary, I will poke the bear, scratch the wound, do whatever is necessary to, like Inanna (from “The Descent of Inanna”), be stripped of all that I cling to or identify with, only to dive deep into my underworld. Why? Because when I come back up for air, almost numb from the pain, I can breathe again. And it all becomes worth it, not only because of the relief I experience but also because I respect the depths I go to, to be certain I have honored my truth.

9.As a self-taught photographer, what were some of the biggest challenges you faced in developing your style?

This is a big and important question. I have faced many, many challenges in this process: Impostor syndrome, a deep-seated fear of “being seen” (or perceived), needing “permission” or acknowledgment from people close to me to consider what I had done as something worthy or disposable.

For many, many years, a shadow hung over me that told me I could never call myself a photographer (much less an artist) because I “had no idea what I was doing.” I have learned to use my camera in quite a torturous way. Many times, ending up mentally and spiritually battered and bruised, and even putting it away “definitely” for months at a time. I would chronically compare myself with the many photographers around me, and not only with the ones I admired. Anyone would seem intimidating to me, and I would shy away from any conversation that would require me to mention I was a photographer.

And the less-than-kind male voices that destroyed my weak self-confidence were the ones I kept at hand, rather than the voices of those who admired my work and my process.

It has been a long process, but although I had a “recognizable style” that came naturally to me before, my true, loud voice came later. There is a clear synchronicity between the moment my world collapsed, my mind broke, and the moment I reached for my camera as a form of survival. Maybe it was the anger in me that made me find my proud, unapologetic voice and the flexibility and freedom to never cease to explore all the different shades and phases my voice and style have the right to exist and explore in.

10.What has been the most surprising or transformative moment in your artistic career?

Although I shoot digitally, I can’t really see much of what I’m shooting because my eyesight is less than ideal. I take my glasses off while I shoot, and although I do put them back on to be able to adjust camera settings and have a basic view of what I’m working on, I never really, truly SEE what I have created until I download it to my computer.

I think the most surprising and transformative moments for me arise when I see the culmination of hours of work on my computer screen and feel a surge of excitement, intensity, and even a righteous (delightful) anger. As I become more vocal and authentic, rather than retreating or becoming “less theatrical,” I begin to recognize how these moments have come together to reshape me. Deeply. Over time, they’ve empowered me to stand tall in my true voice and my deep need to create. Descartes’s “I think, therefore I am” has evolved within me into “I create, therefore I am.” Art is not just my expression—it’s my breath, my healing, and my rebellion against silence. I am an artist— and I embrace this truth with pride.